Circuses are not my favorite, but Sawdust and Tinsel is about a circus the way La Strada is about a circus, which is to say not much. In fact, the films share a lot in common, as both feature rundown circuses struggling to get by and gruff older men attached to younger women. Of course, those women aren't exactly the same, and Bergman's film is more about issues of identity and jealousy than loyalty and love. Fellini was a fundamentally more upbeat director than Bergman (which isn't saying much) and this film, like many of his films, ends up being extremely sad and emotionally wrenching. However, Sawdust and Tinsel isn't a masterpiece, but instead a film in which a great director comes into his own. This is Bergman's 13th film, but it feels like a partially formed version of many of his films to come, a toe dip, if you will, into the themes he would continue to explore throughout his career. Because of this, it's an interesting historical artifact, and a reasonably strong film. But it would not be in the collection if it had been made by anyone else.

Monday, October 25, 2010

#412: Sawdust and Tinsel

Circuses are not my favorite, but Sawdust and Tinsel is about a circus the way La Strada is about a circus, which is to say not much. In fact, the films share a lot in common, as both feature rundown circuses struggling to get by and gruff older men attached to younger women. Of course, those women aren't exactly the same, and Bergman's film is more about issues of identity and jealousy than loyalty and love. Fellini was a fundamentally more upbeat director than Bergman (which isn't saying much) and this film, like many of his films, ends up being extremely sad and emotionally wrenching. However, Sawdust and Tinsel isn't a masterpiece, but instead a film in which a great director comes into his own. This is Bergman's 13th film, but it feels like a partially formed version of many of his films to come, a toe dip, if you will, into the themes he would continue to explore throughout his career. Because of this, it's an interesting historical artifact, and a reasonably strong film. But it would not be in the collection if it had been made by anyone else.

#74: Vagabond

This movie is probably my favorite Varda film yet, a deeply sad and moving portrayal of a human being on the margins. It features a remarkable performance by Sandrine Bonnaire (at just 17), who also gave an excellent performance two years earlier in À nos amours, and includes a number of professional and amateur actors who form a stunning and memorable ensemble. But the movie is entirely Varda's, and it's a remarkable display of thirty years of film experience.

Vagabond begins with Bonnaire's character, whom we later find out was named Mona, being found dead in a ditch by the side of the road. The remainder of the film is a flashback to her final months, intercut with documentary style thoughts of the people she has encountered. These thoughts are always offered once Mona has already moved on, and this to me is the essential structure of the film, perpetually one step behind this character, struggling to understand someone who lives life in a way that we are all either too smart or too cowardly to take up ourselves. Unlike junkies or criminals or crazy people, drifters are immediately understandable to people because their inability to take on responsibility or make an emotional connection mirrors our own frustration with these aspects of our lives, and the notion of total freedom is an unavoidable temptation. We all wish we had the courage to do it, even though we simultaneously know that it would never be as exciting or enjoyable as it seems. Much like poor people prefer to keep the taxes for rich people low because they might be rich someday, we hold out hope that we might one day take to the road, meet interesting people, take on interesting jobs, and live our lives with no responsibilities and no baggage.

Varda understands both sides of this perception, and makes no judgments on Mona or her way of life, instead preferring to struggle with her own place in society. It's what makes Vagabond more than an excellent character study, instead morphing it into an examination of our own fears and dreams. We reject dirt because we know we have to survive in our society, we believe in a hard day's work because if we don't then we'll starve. We insist on turning our backs on Mona, because there are too many Monas to help. One of the Criterion essays compared the film to Citizen Kane, and while the structural comparison is obvious, the more insightful point is that both films aren't so much about their titular characters as they are about the societies that surround them. Vagabond isn't about how someone becomes a drifter (we only learn that in vague terms here), just as Citizen Kane certainly isn't about why people become rich. Instead, the film is about our own place in society, the human connections we struggle to make, and a desperate desire to understand our place in the world.

Thursday, October 21, 2010

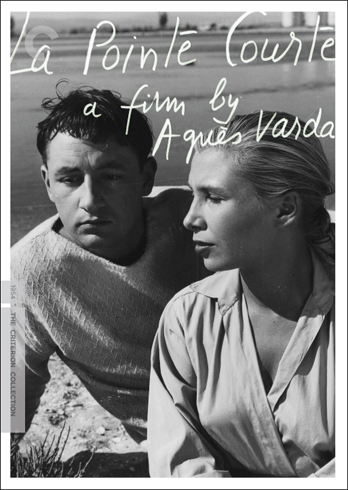

#419: La Pointe Courte

(Agnès Varda, 1955)

Easily one of the greatest female directors of all time, Agnès Varda is also (not coincidentally) one of the most underrated directors of all time, and I say that having only seen two of her designated classics (the other, Vagabond, is sitting on my DVD player) and a couple of her later works. Cléo From 5 to 7 is a masterpiece, one of the great films of the New Wave, and an extremely influential film. But it's this movie - which I actually didn't particularly enjoy - that is (or rather, should be) her claim to historical significance. La Pointe Courte was made in 1954 (it was released in '55) five years before The 400 Blows became an international sensation and reinvigorated French cinema. This movie isn't as good as that one (just my opinion), but it's every bit as revolutionary, not just because it uses amateur actors shooting on location detailing everyday life, but because it attempts to introduce a new language of film, a new way of looking at narrative.

It's the kind of movie that can't help but bring up serious issues of gender. Varda tells her story in such a confident and sprawling fashion that, had it been directed by a man, I have no doubt that it would be considered "ballsy," "defiant," and a rejection of conventional French film in many of the ways that the work of Truffaut and Godard were in the ensuing years. But the combination of male bravado (in personality rather than filmmaking, for inarguably La Pointe Courte is not a timid movie) and the general sexist tendency to move towards the biggest presence in the room then and even now has prevented most people from acknowledging the film's impact on the history of the artform. Certainly, statements like the one Godard made regarding Truffaut's first film - in which he basically said we and our swinging dicks are coming, and don't get in our fucking way - had a certain ability to transfix the cinema crowd at a time when they were looking for something different. So it's not the fact that La Pointe Courte didn't have the capacity to shock audiences and upend their preconceived notions about French cinema, but rather that Varda was most likely uninterested in crowing about it, and unlikely to be viewed as the white knight to the rescue of a film culture that was treading water. (As an aside, there is also the historical context in which the film was made, of course, that had less to do with gender. The year before La Pointe Courte was made, Max Ophüls made one of the greatest films of all time in France, The Earrings of Madame De... and Jaques Tati introduced his timeless M. Hulot in M. Hulot's Holiday. Surely, French cinema was far from dead. By the time Truffaut and Godard finally decided to roll out of bed and make a film, the time was right for revolution.)

Despite my soap box, you may have noticed that I said I didn't particularly like La Pointe Courte. It's not that I think it's a bad film, but instead just one that didn't especially move me, and one with which I had a hard time connecting. Like Last Year at Marienbad - which has a direct connection to the film, as Alain Renais was the editor here - the movie turns a simple story of a relationship into a dream-like exploration of human interaction, complete with stilted line readings and expressionistic framing. And like Amarcord, the film is more a portrait of a town and a way of life than a specific person or persons with one distinct storyline. But unlike either of those films, it doesn't concern itself with issues of cinema - memory, perception, spacial and visual construct - that I find perhaps the most intriguing elements of each of those films. Varda does play with the balance between narrative film and documentary formats, but it almost feels too seamless to care. Ultimately the film might be too much what it is for me to feel pulled towards any element but the story, and it was a story that didn't impact me.

I don't think you have to love a film to acknowledge its historical importance, and the importance of this film to the coming French cinematic landscape just seems unavoidably huge, towering above any other film I can think of. So the fact that it's so little known and seemingly little loved (it didn't even warrant a separate release from Criterion, being placed instead in a Varda boxset) seems like a grand travesty to me, and one of the glaring examples of women in cinema being pushed aside by their bigger, louder counterparts.

Easily one of the greatest female directors of all time, Agnès Varda is also (not coincidentally) one of the most underrated directors of all time, and I say that having only seen two of her designated classics (the other, Vagabond, is sitting on my DVD player) and a couple of her later works. Cléo From 5 to 7 is a masterpiece, one of the great films of the New Wave, and an extremely influential film. But it's this movie - which I actually didn't particularly enjoy - that is (or rather, should be) her claim to historical significance. La Pointe Courte was made in 1954 (it was released in '55) five years before The 400 Blows became an international sensation and reinvigorated French cinema. This movie isn't as good as that one (just my opinion), but it's every bit as revolutionary, not just because it uses amateur actors shooting on location detailing everyday life, but because it attempts to introduce a new language of film, a new way of looking at narrative.

It's the kind of movie that can't help but bring up serious issues of gender. Varda tells her story in such a confident and sprawling fashion that, had it been directed by a man, I have no doubt that it would be considered "ballsy," "defiant," and a rejection of conventional French film in many of the ways that the work of Truffaut and Godard were in the ensuing years. But the combination of male bravado (in personality rather than filmmaking, for inarguably La Pointe Courte is not a timid movie) and the general sexist tendency to move towards the biggest presence in the room then and even now has prevented most people from acknowledging the film's impact on the history of the artform. Certainly, statements like the one Godard made regarding Truffaut's first film - in which he basically said we and our swinging dicks are coming, and don't get in our fucking way - had a certain ability to transfix the cinema crowd at a time when they were looking for something different. So it's not the fact that La Pointe Courte didn't have the capacity to shock audiences and upend their preconceived notions about French cinema, but rather that Varda was most likely uninterested in crowing about it, and unlikely to be viewed as the white knight to the rescue of a film culture that was treading water. (As an aside, there is also the historical context in which the film was made, of course, that had less to do with gender. The year before La Pointe Courte was made, Max Ophüls made one of the greatest films of all time in France, The Earrings of Madame De... and Jaques Tati introduced his timeless M. Hulot in M. Hulot's Holiday. Surely, French cinema was far from dead. By the time Truffaut and Godard finally decided to roll out of bed and make a film, the time was right for revolution.)

Despite my soap box, you may have noticed that I said I didn't particularly like La Pointe Courte. It's not that I think it's a bad film, but instead just one that didn't especially move me, and one with which I had a hard time connecting. Like Last Year at Marienbad - which has a direct connection to the film, as Alain Renais was the editor here - the movie turns a simple story of a relationship into a dream-like exploration of human interaction, complete with stilted line readings and expressionistic framing. And like Amarcord, the film is more a portrait of a town and a way of life than a specific person or persons with one distinct storyline. But unlike either of those films, it doesn't concern itself with issues of cinema - memory, perception, spacial and visual construct - that I find perhaps the most intriguing elements of each of those films. Varda does play with the balance between narrative film and documentary formats, but it almost feels too seamless to care. Ultimately the film might be too much what it is for me to feel pulled towards any element but the story, and it was a story that didn't impact me.

I don't think you have to love a film to acknowledge its historical importance, and the importance of this film to the coming French cinematic landscape just seems unavoidably huge, towering above any other film I can think of. So the fact that it's so little known and seemingly little loved (it didn't even warrant a separate release from Criterion, being placed instead in a Varda boxset) seems like a grand travesty to me, and one of the glaring examples of women in cinema being pushed aside by their bigger, louder counterparts.

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

#80: The Element of Crime

(Lars Von Trier, 1984)

Sigh.

Well, I will say one thing about Criterion and their insistence on liking Von Trier: it's not an overnight phenomenon. As an early addition to their DVD run, The Element of Crime is a strange frustrating installment, a bizarre mix of uninteresting trashy noir and technically impressive (but ultimately hollow) cinematic style. The movie looks beautiful, and by beautiful I mean horrible, disgusting, unappealing, and unlikable. Perhaps this is what I meant Hunger should look like, which makes me doubt why I was complaining about that film's appearance anyway. Who wants to look at crap when they can look at beauty?

And, really, The Element of Crime is crap. It's partially crap on purpose, and it's also crap for a lot of reasons I have problems with Trier's work. The two that most bother me with his work are that it's incredibly sexist, and it has a disdain for conventional filmmaking that is only matched by its constant derivation of material from classic filmmakers. But really it's crap because Trier is an incredibly talented filmmaker who has occasionally stumbled into great work, seemingly unintentionally. I don't say that because he is clueless, but instead because I genuinely don't think Trier has any interest in entertaining an audience, or even really engaging with one. He just wants to be an asshole. Sometimes assholes make great art because what they say needs to be said. I personally think that's happened a few times with Trier, but I wouldn't be surprised if I was wrong.

Sigh.

Well, I will say one thing about Criterion and their insistence on liking Von Trier: it's not an overnight phenomenon. As an early addition to their DVD run, The Element of Crime is a strange frustrating installment, a bizarre mix of uninteresting trashy noir and technically impressive (but ultimately hollow) cinematic style. The movie looks beautiful, and by beautiful I mean horrible, disgusting, unappealing, and unlikable. Perhaps this is what I meant Hunger should look like, which makes me doubt why I was complaining about that film's appearance anyway. Who wants to look at crap when they can look at beauty?

And, really, The Element of Crime is crap. It's partially crap on purpose, and it's also crap for a lot of reasons I have problems with Trier's work. The two that most bother me with his work are that it's incredibly sexist, and it has a disdain for conventional filmmaking that is only matched by its constant derivation of material from classic filmmakers. But really it's crap because Trier is an incredibly talented filmmaker who has occasionally stumbled into great work, seemingly unintentionally. I don't say that because he is clueless, but instead because I genuinely don't think Trier has any interest in entertaining an audience, or even really engaging with one. He just wants to be an asshole. Sometimes assholes make great art because what they say needs to be said. I personally think that's happened a few times with Trier, but I wouldn't be surprised if I was wrong.

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

#77: And God Created Woman

(Roger Vadim, 1956)

And God Created Woman is not a good movie. It is, in purely objective terms, perhaps one of the most mediocre films in the Criterion catalog, a passably directed, poorly acted, inadvertently attractive movie. The fact that it sits next to Wild Strawberries and The Seven Samurai in the collection is entirely a testament to Brigitte Bardot.

Well, check that, Brigitte Bardot's body. See, Bardot isn't much of an actress. Say what you want about Marilyn Monroe, but she displayed more energy, more sizzle, more style and wit in The Seven Year Itch a year earlier than Bardot could probably have mustered in an entire career - actually, definitely, since she tried and could never quite do it (undoubtedly, her most relevant performance was in Godard's aptly titled masterpiece Contempt, where Bardot's natural gifts are almost used against her - thankfully she quit while she was behind in the early 70s). So I say with all due respect to sex goddesses that Bardot has little to offer in And God Created Woman but her body.

The film itself is not much better, sporting a melodramatic plot that would have made Douglas Sirk roll his eyes and a jumbled mishmash of dated sexual and racial politics that is so ancient you can almost hear the creaking underneath a line like, "She's brave enough to do what she wants, when she wants." Chuck Stephens's essay which accompanied the Criterion release of the film ten years ago barely even acknowledges its existence: the author discusses the actual movie for just one paragraph, changes the conversation to the almost criminally superior Contempt for another, and devotes a full six surrounding paragraphs to Bardot specifically. "Eventually," he writes, undoubtedly while holding back laughter, "Juliette will brave fire and sea, ecstasy and despair, and - as a result of her unquenchable desire - erupt into a kind of Mambo-inspired madness." So, um, yeah. People wonder why Armageddon is in the collection.

There are a few well-executed moments in And God Created Woman. The scene of Bardot coming down to her new husband's family, who are all waiting for the couple to eat dinner with them, wearing only a robe and promptly gathering up food and carrying it back to the bedroom is fucking ballsy. It's just a "holy shit, this lady is punk rock" kind of moment. But for every moment like that, there's one where her character feels hopelessly tied to gender stereotypes, like when she knows doom is on the horizon when her brother-in-law moves home. Is this lady kick-ass or vulnerable? Is she supposed to be tamed or can nothing destroy her? Are we really meant to take away from the film that wild women will destroy the men who love them, and only through forgiveness can they both be happy?

Just to be clear, I am entirely aware that Brigitte Bardot is an incredibly beautiful woman. I just happen to feel this is not enough to sustain a film. It's impossible for me to view And God Created Woman from the perspective of a person who lived the culture of 1956. So I don't know what it would have been like to see a woman portrayed in this way for the first time in film. Obviously Vadim knew what he was doing, naming the film what he named it and shooting Bardot (his then wife, dude was creepy btw) the way he shot her. But from a modern perspective, all the sex that's left is a lingering feeling that something here was dirty that isn't anymore. Instead of feeling alive with energy, the movie feels long dead, the casualty of new paradigms of sexual politics and sexual cinema.

And God Created Woman is not a good movie. It is, in purely objective terms, perhaps one of the most mediocre films in the Criterion catalog, a passably directed, poorly acted, inadvertently attractive movie. The fact that it sits next to Wild Strawberries and The Seven Samurai in the collection is entirely a testament to Brigitte Bardot.

Well, check that, Brigitte Bardot's body. See, Bardot isn't much of an actress. Say what you want about Marilyn Monroe, but she displayed more energy, more sizzle, more style and wit in The Seven Year Itch a year earlier than Bardot could probably have mustered in an entire career - actually, definitely, since she tried and could never quite do it (undoubtedly, her most relevant performance was in Godard's aptly titled masterpiece Contempt, where Bardot's natural gifts are almost used against her - thankfully she quit while she was behind in the early 70s). So I say with all due respect to sex goddesses that Bardot has little to offer in And God Created Woman but her body.

The film itself is not much better, sporting a melodramatic plot that would have made Douglas Sirk roll his eyes and a jumbled mishmash of dated sexual and racial politics that is so ancient you can almost hear the creaking underneath a line like, "She's brave enough to do what she wants, when she wants." Chuck Stephens's essay which accompanied the Criterion release of the film ten years ago barely even acknowledges its existence: the author discusses the actual movie for just one paragraph, changes the conversation to the almost criminally superior Contempt for another, and devotes a full six surrounding paragraphs to Bardot specifically. "Eventually," he writes, undoubtedly while holding back laughter, "Juliette will brave fire and sea, ecstasy and despair, and - as a result of her unquenchable desire - erupt into a kind of Mambo-inspired madness." So, um, yeah. People wonder why Armageddon is in the collection.

There are a few well-executed moments in And God Created Woman. The scene of Bardot coming down to her new husband's family, who are all waiting for the couple to eat dinner with them, wearing only a robe and promptly gathering up food and carrying it back to the bedroom is fucking ballsy. It's just a "holy shit, this lady is punk rock" kind of moment. But for every moment like that, there's one where her character feels hopelessly tied to gender stereotypes, like when she knows doom is on the horizon when her brother-in-law moves home. Is this lady kick-ass or vulnerable? Is she supposed to be tamed or can nothing destroy her? Are we really meant to take away from the film that wild women will destroy the men who love them, and only through forgiveness can they both be happy?

Just to be clear, I am entirely aware that Brigitte Bardot is an incredibly beautiful woman. I just happen to feel this is not enough to sustain a film. It's impossible for me to view And God Created Woman from the perspective of a person who lived the culture of 1956. So I don't know what it would have been like to see a woman portrayed in this way for the first time in film. Obviously Vadim knew what he was doing, naming the film what he named it and shooting Bardot (his then wife, dude was creepy btw) the way he shot her. But from a modern perspective, all the sex that's left is a lingering feeling that something here was dirty that isn't anymore. Instead of feeling alive with energy, the movie feels long dead, the casualty of new paradigms of sexual politics and sexual cinema.

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

#72: Le Million

(René Clair, 1931)

I almost hated Le Million. OK, maybe not hated, but it's never a good idea to thrust a musical on me unexpected. I had no idea there was singing involved in Le Million, and when people randomly break into song, well, I tend to get angry. The first half of the movie didn't go particularly well for me. "Why can't they just talk?" was a common refrain.

Then I relaxed and let an obviously brilliant movie made by a clearly innovative and inventive director wash over me. Le Million isn't contemporary the way some films will remain forever. It is most certainly of its time. But it's light and fresh as the day it was made, more of an anachronism than an artifact whose appeal has long since been lost to time. I was genuinely interested in how the film would end, and completely delighted by the process of getting there.

The most famous scene in Le Million is probably the scene in which the jacket containing the million dollar ticket is tossed around to a completely non-diagetic football soundtrack. It's incredibly smart, and just as funny as the day it was made. Yet it's also sort of astonishing if you think about it in the context of film history. Imagine, only a few years after sound was established in film, using it as a comedic punchline, playing off the story told visually. This was an entirely new form of comedy, something that, to my knowledge, had never been done before. There are only a few people in film - in history of any kind - who can honestly be credited with the invention of a new way of presenting humor. It makes Clair a much more relevant artist than he has often gotten credit for, as he is often forgotten as a pioneer of French cinema rather than a truly ingenious director who can measure up with other artists.

Le Million isn't quite perfect. I think it was a mistake to give away the ending of the film at the beginning, and I don't understand why his friend is such a dick if there isn't a pay off at the end where he has a chance to redeem himself. But it's still the kind of movie that reminds you that modern filmmakers are standing on the shoulders of giants, many of whom haven't been surpassed yet.

I almost hated Le Million. OK, maybe not hated, but it's never a good idea to thrust a musical on me unexpected. I had no idea there was singing involved in Le Million, and when people randomly break into song, well, I tend to get angry. The first half of the movie didn't go particularly well for me. "Why can't they just talk?" was a common refrain.

Then I relaxed and let an obviously brilliant movie made by a clearly innovative and inventive director wash over me. Le Million isn't contemporary the way some films will remain forever. It is most certainly of its time. But it's light and fresh as the day it was made, more of an anachronism than an artifact whose appeal has long since been lost to time. I was genuinely interested in how the film would end, and completely delighted by the process of getting there.

The most famous scene in Le Million is probably the scene in which the jacket containing the million dollar ticket is tossed around to a completely non-diagetic football soundtrack. It's incredibly smart, and just as funny as the day it was made. Yet it's also sort of astonishing if you think about it in the context of film history. Imagine, only a few years after sound was established in film, using it as a comedic punchline, playing off the story told visually. This was an entirely new form of comedy, something that, to my knowledge, had never been done before. There are only a few people in film - in history of any kind - who can honestly be credited with the invention of a new way of presenting humor. It makes Clair a much more relevant artist than he has often gotten credit for, as he is often forgotten as a pioneer of French cinema rather than a truly ingenious director who can measure up with other artists.

Le Million isn't quite perfect. I think it was a mistake to give away the ending of the film at the beginning, and I don't understand why his friend is such a dick if there isn't a pay off at the end where he has a chance to redeem himself. But it's still the kind of movie that reminds you that modern filmmakers are standing on the shoulders of giants, many of whom haven't been surpassed yet.

Monday, October 4, 2010

#20: Sid and Nancy

(Alex Cox, 1986)

Sid and Nancy is, as many people have pointed out in their reviews and essays on the film, a tale of two movies. The first is a mood piece about the London punk scene of the late 1970s, and it's only moderately successful. The second is a startlingly disturbing and moving portrayal of a love affair torn apart by many of the things which instigated it in the first place. As the couple descends deeper into their addiction and becomes more and more separated from the reality of their circumstances, the film takes on the sort of anti-Hollywood fantasy sheen reserved only for the truly brilliant iconoclastic filmmakers, a group which undoubtedly includes Cox.

This final half is also benefited by having two excellent performances from Gary Oldman and Chloe Webb, two performers whose careers have gone in different directions. The final scene between them, in which Oldman may or may not stab Webb, is truly harrowing, the kind of dark culmination of a film that is earned through an hour plus of character establishment, and then paid off by impeccable staging and gut-wrenching acting. Combined with Walker, Sid and Nancy makes Alex Cox one of the most blatantly unique and independent voices in the collection.

Sid and Nancy is, as many people have pointed out in their reviews and essays on the film, a tale of two movies. The first is a mood piece about the London punk scene of the late 1970s, and it's only moderately successful. The second is a startlingly disturbing and moving portrayal of a love affair torn apart by many of the things which instigated it in the first place. As the couple descends deeper into their addiction and becomes more and more separated from the reality of their circumstances, the film takes on the sort of anti-Hollywood fantasy sheen reserved only for the truly brilliant iconoclastic filmmakers, a group which undoubtedly includes Cox.

This final half is also benefited by having two excellent performances from Gary Oldman and Chloe Webb, two performers whose careers have gone in different directions. The final scene between them, in which Oldman may or may not stab Webb, is truly harrowing, the kind of dark culmination of a film that is earned through an hour plus of character establishment, and then paid off by impeccable staging and gut-wrenching acting. Combined with Walker, Sid and Nancy makes Alex Cox one of the most blatantly unique and independent voices in the collection.

Friday, October 1, 2010

#66: The Orphic Trilogy

(Jean Cocteau, 1930-1959)

It's hard to think of films made 30 years apart with no plot similarities as part of the same trilogy. Certainly when Cocteau made The Blood of a Poet he hadn't intended to make two more films in the same series, and really these films are only thought of as a trilogy because Cocteau himself declared it.

Of course, they are all connected, both thematically and aesthetically, and certainly Testament of Orpheus can be seen as a unique kind of sequel to Orpheus, wherein the creator is asked to answer for his creations. Part of what makes it so easy to attach them to each other is the fact that each explores the same things at many points, and making them a series is much easier than explaining why you repeated yourself. Cocteau subtitled the last film "Do Not Ask Me Why," intending for people to take these films at their face value and stop trying to find a real answer to the mysteries they presented. It's far too easy in art these days to need a "right" interpretation of something, especially since many artists come from school where they are often forced to explain the motivation behind their work. Cocteau was a great filmmaker because he let the work speak for itself, especially when, as was the case with this trilogy, it was speaking of itself.

Links to individual reviews:

The Blood of a Poet

Orpheus

Testament of Orpheus

It's hard to think of films made 30 years apart with no plot similarities as part of the same trilogy. Certainly when Cocteau made The Blood of a Poet he hadn't intended to make two more films in the same series, and really these films are only thought of as a trilogy because Cocteau himself declared it.

Of course, they are all connected, both thematically and aesthetically, and certainly Testament of Orpheus can be seen as a unique kind of sequel to Orpheus, wherein the creator is asked to answer for his creations. Part of what makes it so easy to attach them to each other is the fact that each explores the same things at many points, and making them a series is much easier than explaining why you repeated yourself. Cocteau subtitled the last film "Do Not Ask Me Why," intending for people to take these films at their face value and stop trying to find a real answer to the mysteries they presented. It's far too easy in art these days to need a "right" interpretation of something, especially since many artists come from school where they are often forced to explain the motivation behind their work. Cocteau was a great filmmaker because he let the work speak for itself, especially when, as was the case with this trilogy, it was speaking of itself.

Links to individual reviews:

The Blood of a Poet

Orpheus

Testament of Orpheus

#69: Testament of Orpheus

(Jean Cocteau, 1959)

I loved this movie for a good portion of its running time, but by the end, I was a little bored. It reminded me of Deconstructing Harry a little bit (which I'm sure was intentional on Woody Allen's part) but it also reminded me that movies were already extremely self-referential in 1959. The opening sequence of Cocteau being unstuck in time is a fascinating twenty or so minutes of film, and there are plenty of other great moments. But there ends up being a few too many backwards shots and a little too much cryptic talking by the end.

Side note: it was a surprise and pleasure to see Jean-Pierre Léaud with a cameo in the film, which was made right after his most famous film, The 400 Blows (and apparently Cocteau, having run out of money, used Truffaut's prize money from that film to finish this one). Léaud is so strongly associated with the New Wave that seeing him in a Cocteau film is a bit like being unstuck in time in its own way.

I loved this movie for a good portion of its running time, but by the end, I was a little bored. It reminded me of Deconstructing Harry a little bit (which I'm sure was intentional on Woody Allen's part) but it also reminded me that movies were already extremely self-referential in 1959. The opening sequence of Cocteau being unstuck in time is a fascinating twenty or so minutes of film, and there are plenty of other great moments. But there ends up being a few too many backwards shots and a little too much cryptic talking by the end.

Side note: it was a surprise and pleasure to see Jean-Pierre Léaud with a cameo in the film, which was made right after his most famous film, The 400 Blows (and apparently Cocteau, having run out of money, used Truffaut's prize money from that film to finish this one). Léaud is so strongly associated with the New Wave that seeing him in a Cocteau film is a bit like being unstuck in time in its own way.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)