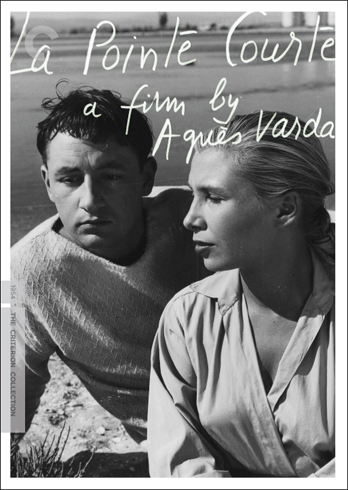

(Agnès Varda, 1955)

Easily one of the greatest female directors of all time, Agnès Varda is also (not coincidentally) one of the most underrated directors of all time, and I say that having only seen two of her designated classics (the other, Vagabond, is sitting on my DVD player) and a couple of her later works. Cléo From 5 to 7 is a masterpiece, one of the great films of the New Wave, and an extremely influential film. But it's this movie - which I actually didn't particularly enjoy - that is (or rather, should be) her claim to historical significance. La Pointe Courte was made in 1954 (it was released in '55) five years before The 400 Blows became an international sensation and reinvigorated French cinema. This movie isn't as good as that one (just my opinion), but it's every bit as revolutionary, not just because it uses amateur actors shooting on location detailing everyday life, but because it attempts to introduce a new language of film, a new way of looking at narrative.

It's the kind of movie that can't help but bring up serious issues of gender. Varda tells her story in such a confident and sprawling fashion that, had it been directed by a man, I have no doubt that it would be considered "ballsy," "defiant," and a rejection of conventional French film in many of the ways that the work of Truffaut and Godard were in the ensuing years. But the combination of male bravado (in personality rather than filmmaking, for inarguably La Pointe Courte is not a timid movie) and the general sexist tendency to move towards the biggest presence in the room then and even now has prevented most people from acknowledging the film's impact on the history of the artform. Certainly, statements like the one Godard made regarding Truffaut's first film - in which he basically said we and our swinging dicks are coming, and don't get in our fucking way - had a certain ability to transfix the cinema crowd at a time when they were looking for something different. So it's not the fact that La Pointe Courte didn't have the capacity to shock audiences and upend their preconceived notions about French cinema, but rather that Varda was most likely uninterested in crowing about it, and unlikely to be viewed as the white knight to the rescue of a film culture that was treading water. (As an aside, there is also the historical context in which the film was made, of course, that had less to do with gender. The year before La Pointe Courte was made, Max Ophüls made one of the greatest films of all time in France, The Earrings of Madame De... and Jaques Tati introduced his timeless M. Hulot in M. Hulot's Holiday. Surely, French cinema was far from dead. By the time Truffaut and Godard finally decided to roll out of bed and make a film, the time was right for revolution.)

Despite my soap box, you may have noticed that I said I didn't particularly like La Pointe Courte. It's not that I think it's a bad film, but instead just one that didn't especially move me, and one with which I had a hard time connecting. Like Last Year at Marienbad - which has a direct connection to the film, as Alain Renais was the editor here - the movie turns a simple story of a relationship into a dream-like exploration of human interaction, complete with stilted line readings and expressionistic framing. And like Amarcord, the film is more a portrait of a town and a way of life than a specific person or persons with one distinct storyline. But unlike either of those films, it doesn't concern itself with issues of cinema - memory, perception, spacial and visual construct - that I find perhaps the most intriguing elements of each of those films. Varda does play with the balance between narrative film and documentary formats, but it almost feels too seamless to care. Ultimately the film might be too much what it is for me to feel pulled towards any element but the story, and it was a story that didn't impact me.

I don't think you have to love a film to acknowledge its historical importance, and the importance of this film to the coming French cinematic landscape just seems unavoidably huge, towering above any other film I can think of. So the fact that it's so little known and seemingly little loved (it didn't even warrant a separate release from Criterion, being placed instead in a Varda boxset) seems like a grand travesty to me, and one of the glaring examples of women in cinema being pushed aside by their bigger, louder counterparts.

No comments:

Post a Comment