(John Schlesinger, 1963)

Billy Liar is

The Graduate four years earlier and set in small-town England. Actually, it's better than

The Graduate. The film follows Billy Fisher, a professional underachiever who lives with his parents, sleepwalks his way through a meaningless job, and longs for a showbiz gig in the big city. To avoid sinking into a deep depression, Billy constructs elaborate fictions, some of which he keeps to himself, others which he shares with other people. Billy is engaged to two different girls, hiding a mild embezzlement scheme from his employer, and convincing everyone that his train finally came in and he's going to write for a big comic in London. Naturally, nothing goes as planned.

I'm going to admit a number of embarrassing things in succession: I had no idea John Schlesinger made such a splash in England before making the best picture winning

Midnight Cowboy; I initially had thought Alec Guinness was in this movie; and I expected to find it moderately amusing at best. I was way off on all three counts, and the movie turned into one of those most pleasant surprises: the unexpected masterpiece. The film has a wry sense of humor in the most appealingly British way, and it's shot beautifully - this is, by the way, one of Criterion's best early transfers that I've seen, though it is now out of print. But the real appeal of the film is its vivid portrayal of Billy which I became totally invested in and consequently moved by.

Billy Liar, like

The Graduate after it, is meant to be relatable to its audience. But despite the early moments when Dustin Hoffman returns from college to face his parents and their friends, Mike Nichols's film seems much more about my parents than about me. Maybe it's too iconic for me to see the film as anything but a representation of its time, whereas I am able to see

Billy Liar shed of any baggage the canon might impart. The movie then feels much more universal, and while I can't entirely relate with the degree to which Billy struggles with his fears, I can see in it a fundamental challenge of youth as it slowly melts away and becomes regrets.

I often think about the difference between films made regarding the beginning of life and films regarding the end of it. I think the former are more appealing to viewers for two reasons. The first is that everyone can compare their own experience to the experience of the young people in the film, because everyone has been a young person, but not everyone has yet been in the twilight of their life. The second is that young people are inevitably concerned with the future, creating new realities to shape their world and the world of people in future generations. This makes movies about young people feel fresh when they are created, because the experience of that generation - whether it's depicted in

Rebel Without a Cause or

Fast Times at Ridgemont High - is unique and immediately relevant. In contrast, movies about old people are almost always looking back to the past, grappling with larger philosophical issues - think

Wild Strawberries or

On Golden Pond. This makes them timeless, but it also makes them feel less alive: the latter two films I mentioned are certainly quieter, more subtle explorations of humanity than the bombastic teenage melodramas made in relatively contemporary times.

This is all to say that

Billy Liar depicts a moment in youth culture to which I have little connection and every connection. The way the characters behave is totally foreign, but why they behave that way is perhaps the most immediately accessible and personal motivations film can represent. When Billy makes mistakes or has the chance to make the right choice for his life, we feel that much stronger because we see our own crossroads and wonder what might have been. On a more universal level, we are able to understand so much more where a generation found themselves in a crumbling empire just after a world war turned their futures upside-down. This combination makes

Billy Liar exhilarating viewing for anyone who grew up.

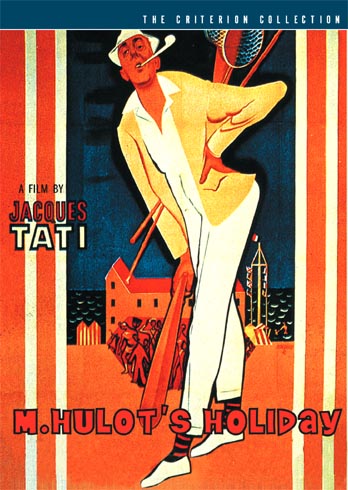

Side note: this is one of the worst Criterion covers ever. It makes the film seem like a Jerry Lewis movie, and the tone doesn't fit at all with the film. Based on a quick search it appears to have been created before Criterion got the rights to the film. As someone who is a self-confessed unquestioning fanboy of Criterion's design aesthetic, I'd like to use this as an excuse for its use here.