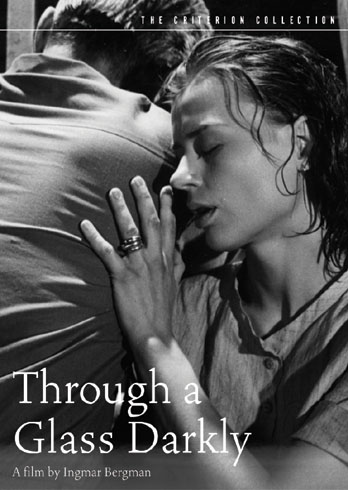

(Ingmar Bergman, 1961)

Through a Glass Darkly is the first film in Ingmar Bergman's Trilogy of Faith, an attempt to marry chamber music, religion, theatrical acting theory, and subtly revolutionary cinematic technique. It's also a masterpiece, one of Bergman's best films. All four performances here are great (though obviously the best is saved for Harriet Andersson in the lead role), and the script is an impeccable merging of intellectual themes and emotional relationships. While the whole movie impressed me, I was especially taken by Andersson's best moments, her silent struggles alone, her desperate calls for help with her husband, and finally, the astonishing, completely enrapturing final monologue describing her encounter with God.

Ultimately, though, the biggest emotional impact came from the father character, played by Gunnar Björnstrand. As a writer myself, I sympathized immensely with his conflict, not only the idea of balancing success with respect (particularly self-respect, which for many people can be most difficult to come by) but the constant moral quandary of separating the personal life from the professional one. His character's greatest dilemma is the one faced by any artist that is seeking for truth through their work. Popular but ultimately rejected as an "important" novelist, he seeks validation with his next novel, based on his daughter's crippling mental illness. He confesses in his journal that he is torn between wanting to help her and examining her descent for the benefit of his work. His daughter reads the confession, sinking deeper into her depression and delusions.

I don't think there is a question of whether or not he is a monster for what he does to his daughter in the film; in my opinion, he clearly is. The more difficult question is whether or not that lack of caring would be necessary in order for him to produce great art. It's not that I'm asking people to forgive artists for their personal indiscretions, but rather that I believe it is important to measure these negative characteristics against the benefit to society as a whole. There are probably far too many artists who believe that being great means being callous; the vast majority of these people are forgotten by history even before they have been rejected by their loved ones. There are plenty more problems with this all too common situation, and the way the film deals with it is both intriguing and extremely affecting.

What I was most reminded of while watching Through a Glass Darkly, however, was the continual gap between what we as viewers enjoy and what we claim to be great. Through a Glass Darkly is by no means an easy viewing, and yet I probably gained more pleasure and enjoyment out of the ideas that the movie provoked in me - and by the sheer excitement of watching a perfect film unfold - that I would inevitably rather watch this film than, say, Two Weeks Notice. Yet put both of them on top of the DVD player after a hard week and, had I never seen either one, I would be unlikely to pick the Bergman film. Probably half of my ten best films list is populated by movies that I either put off watching or have a hard time going back to unless I am prepared (The Last Temptation of Christ, another film about faith, is a perfect example). Why do we put off difficult films, even when difficult films are the ones we love most? Part of this process of watching Criterion's selections has been increasingly realizing the mistake in this choice (while still completely understanding the tendency to want to watch something easy). After watching more than 150 films during this quest, many of my favorite films have been ones I most likely would have never watched otherwise. Through a Glass Darkly joins that list as a solid reminder that often despair can be transcendent, while empty entertainment can never satisfy beyond instant gratification.

No comments:

Post a Comment