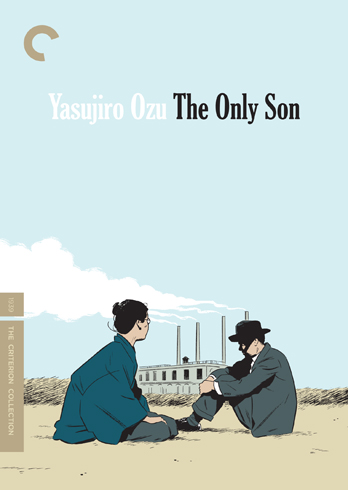

(Yasujiro Ozu, 1936)

There are only a few directors in cinematic history that command the respect of scholars, historians, critics, and lovers of film the way Yasujiro Ozu does. This is in many ways completely understandable to me, and yet I struggle with this hype every time I approach one of his films. The unassuming nature of Ozu's work inevitably clashes with the effusiveness of his supporters' praise. The director created his own cinematic language, molding Eastern cinema the way Griffith had in Hollywood, and he was able to straddle the line between art and commerce remarkably well - particularly in retrospect, when it is difficult to imagine his films being received well by a broad audience. But his work is also deceptively simple. Ozu tells stories about complicated emotions, social dynamics, and the constantly evolving Japanese landscape by stripping his plots down to their bare essentials. It makes his films astonishingly sparse - fitting for their traditional Japanese domestic settings - and teetering on the brink of melodrama.

The Only Son does not stray from the formula - on the contrary, it helped create it. Opening with a young boy's desire to attend middle school, despite his widowed mother's inability to afford his education, the film spans his early years as he grows into adulthood. When his mother comes to visit him in Tokyo, she finds a man who has yet to realize his potential, and both mother and son must come to terms with the sacrifices she made for an investment that does not seem to have paid off.

Even though the film's story stretches over a decade, there are really only four relevant characters in the film: the mother, the son, his wife, and his old teacher who has also moved to Tokyo but found little success. Ozu pauses to poke fun at German cinema briefly, and there are a handful of inside jokes throughout the film, but most of the film is focused in on their simple relationship and its larger allegorical potential. The thing I loved most about this dynamic was how easy it was to identify with each, how desperately they both wanted to do right by each other, and yet how easy it was for them to feel distant from each other because of this pressure. Much like Tokyo Story, there is no evil parent or cruel brother in The Only Son - just people trying to do right by the family they love, weighed down by the pressure of their responsibilities and their economic and social situations.

As an early representation of Ozu's trademark style, The Only Son is perhaps Ozu at his most simplistic, where all of his intentions have been laid bare. I still don't know how I feel about Ozu after watching The Only Son, but I loved every minute of the film. This might mean that viewing his films chronologically is the best way to keep up with his rhythm. Or maybe it takes a few films before you understand his pacing, and I would enjoy the previous Ozu films I've watched even more now. Either way, The Only Son is a great introduction to this most praised - and most foreign - Japanese director.

No comments:

Post a Comment